C-Section Recovery- The First 2 Weeks

Whether you had your C-section scheduled in advance or changed plans quickly on delivery day, we are so happy you and your baby have made it here! Oftentimes, the labor and delivery process can be a blur. In this blog post, we will review some background information about C-sections, briefly discuss the procedure so you can understand the healing process more thoroughly, and then go over short-term implications to be aware of during the immediate two weeks following delivery.

BACKGROUND

Nearly one in every three babies born in the U.S. is delivered via C-section, with rates rising almost 60% over the last 25 years (from 20.7% to 32.9%). Although the surgery can be lifesaving for both mothers and newborns, it should only be performed if vaginal delivery is no longer medically safe. Compared to vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery is associated with a higher risk of maternal complications like infection and subsequent pregnancy complications, as well as significantly increased risk of postoperative complications. To address this, the World Health Organization released guidelines to reduce unnecessary C-sections. These guidelines focus on educational interventions to actively engage women in childbirth preparation and create a more collaborative healthcare model involving a multidisciplinary team. This should include a rehabilitation team to guide recovery and ensure mothers are healing appropriately throughout the crucial short-term period following the procedure and garnering a full long-term rehabilitation.

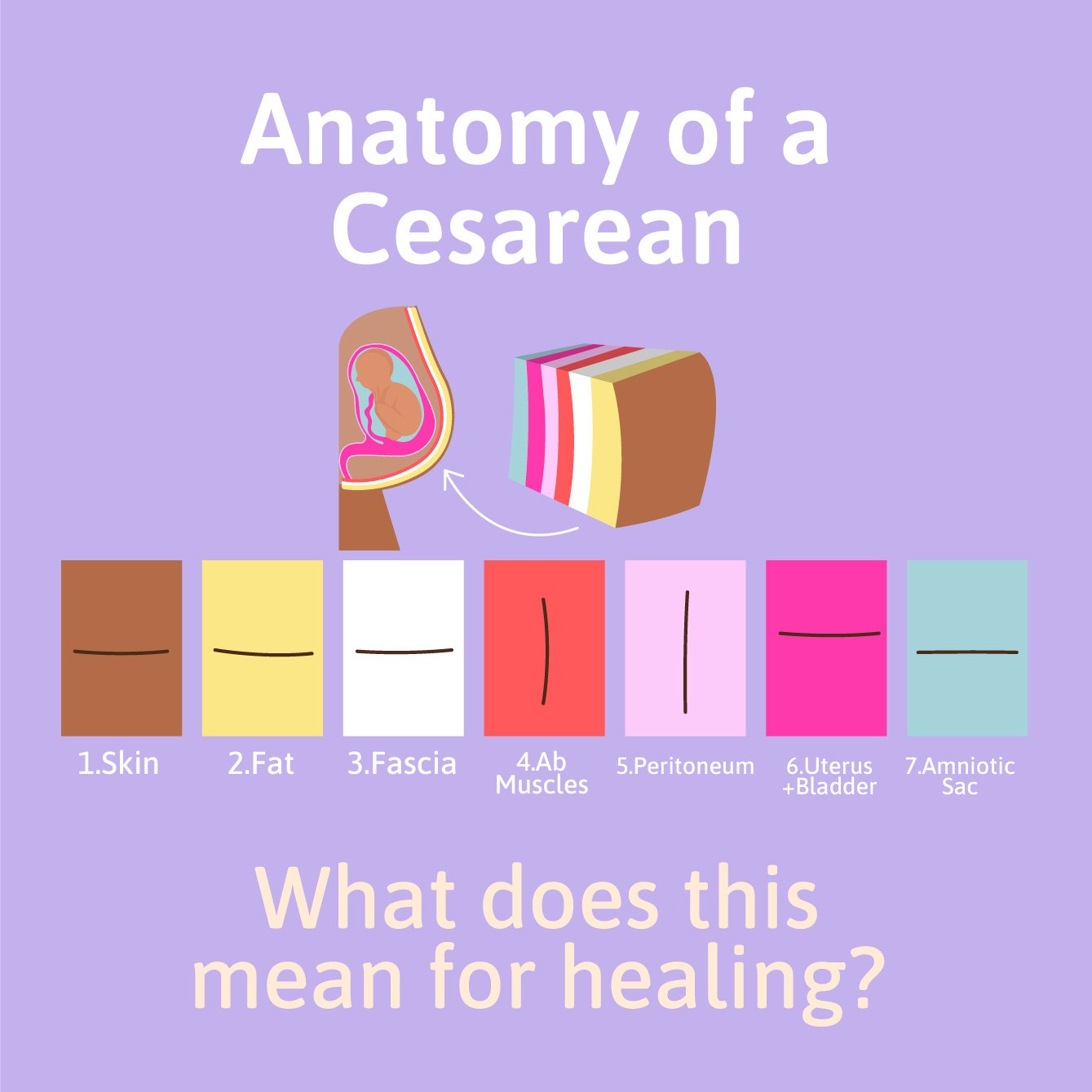

THE PROCEDURE

A C-section is a surgical procedure involving an incision through the lower abdomen to get your baby out of you and into the world. The majority of C-sections performed today are done via a “lower transverse” approach, meaning the incision runs from side to side, horizontally along the lower abdomen. The exact technique used will depend on your surgeon and your individual needs at the time of the procedure. Seven layers of tissue are cut through to get the baby out, illustrated below. The baby is then delivered, followed by the placenta. The incision made in the uterus is then closed. The remaining layers, including the peritoneum, abdominal muscles, and fascia, may or may not be sutured back together, followed by skin closure via sutures or staples. There is debate in the medical community on whether the middle layers should be sewn together or allowed to connect back together on their own. 3 Similarly, there is debate on whether sutures or staples should be used to close the skin. In summary of this debate, wound infection rates have consistently been shown to be lower when sutures are used, however staples require decreased wound closure time and may prevent further blood loss compared to staples.

SHORT TERM IMPLICATIONS

Hospital Stay Length

Because a C-section is a major surgical procedure, recovery typically requires two to three extra days in the hospital to ensure proper incision healing and overall stabilization of your body’s systems. On average, the length of hospital stay for a C-section delivery is twice as long compared to vaginal delivery. 7 If staples were used to close the incision, your hospital stay may require an extra day to allow enough healing to occur before the staples are removed before leaving the hospital. If sutures were used to close the incision, you may be discharged earlier as the sutures will dissolve on their own and do not require manual removal.

2. Pain Management

Postoperative pain (pain after the procedure) in the region where the surgery was performed is expected. If we think about surgery as a scheduled, planned, and precise “injury” to the body, it makes sense why there would be pain afterward. Your skin, fat, and fascia were cut through, and your muscles and internal organs were moved out of the way to get your baby out of you and into the world. A lot happened to make that possible! Do not worry; this will get better over time.

In The Hospital

During your hospital stay, you will be offered high-strength pain medication controlled by either an IV (intravenous) drip or, more likely, a PCA (patient-controlled analgesia) pump immediately following your procedure. As you recover, you and your medical team should communicate openly about your pain levels and make a collective decision on when to wean off of higher-strength opioid medication to transition to lowerstrength pain relievers.

Remember, your insides were just cut open. It is perfectly OK to take high-strength pain medication to be comfortable for a few days. Managing your pain appropriately will allow you to do the two most important things to promote healing during this period: 1) getting up out of bed to walk and move and 2) getting more restful sleep.

Every person and their respective pregnancy and delivery process will be different, so the best advice regarding pain management during the first few days postpartum is to be a part of the medical team's decision-making process and honestly communicate how you feel—advocating for yourself by asking questions and expressing your values, beliefs, and concerns while in the hospital will be integral in ensuring a smoother beginning to your recovery.

At Home

Once you are discharged from the hospital, pain management typically continues with over-the-counter medications that include Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDS, like Advil) and Acetaminophen (Tylenol). Prescriptions for higher-strength medications, like opioids, are typically reserved for extreme cases.

It is important to note that small amounts of the medication(s) you take may pass through your breast milk to your baby. Many medications have been shown to be safe to take while breastfeeding, but it is always best to discuss and disclose all of your medications with your doctor to ensure any risks are mitigated.

3. Wound Management

With any surgical procedure comes the risk of infection, and an infection is the last thing we’d want to worry about when caring for a newborn. To prevent this from happening, the incision site needs to remain clean and covered as it heals. This will reduce the risk of infection and allow for optimal healing. Your doctor and/or delivery nurse(s) should instruct you on properly caring for your wound; the specifics of which can differ slightly from patient to patient. For the first four weeks, you should avoid submerging the incision site, so baths and pools are off-limits. Your wound will take anywhere from four to six weeks to completely close.

How to Spot an Infection

Look out for the following signs and symptoms, as up to 15% of women will develop an infection in their C-section wound.

Contact your OB/GYN immediately if you notice any of the following signs of infection:

Excessive redness and warmth on or around the scar

Puffiness and swelling on or around the scar

Fluid or blood leaking from the wound

Abdominal pain that is not getting better

Foul smelling odor from the incision site

Flu-like symptoms (fever, chills, body aches, fatigue)

4. Lifting Restrictions

The abdominal muscles are involved in much more than crunches at the gym. You may not have known how essential they are to even simple movements like turning a steering wheel or carrying a grocery bag. Lifting objects requires our abdominal muscles to contract to 1) stabilize our spine and 2) manage our guts as the pressure within our intra-abdominal cavity increases when attempting to lift an object. To protect the incision site and reduce the risk of separation/re-tear, it is recommended to avoid lifting any object over 10 pounds for the first six weeks postpartum. Most OB/GYNs recommend limiting your lifting to just your baby over these first four to six weeks. Additionally, while the wound is healing, avoiding driving for the first two weeks is recommended. You should never drive or operate heavy machinery if you are on painkillers. Even if you are not taking heavy medications, turning a steering wheel requires increased abdominal muscle activation, and reacting to traffic, like braking suddenly, can cause increased intra-abdominal pressure.

5. Exercise Limitations and Potentials

Getting back to exercise following a C-section can be slower compared to vaginal delivery due to the increased recovery time needed to heal from surgery. However, this does NOT mean all exercise is off limits. As mentioned, getting out of bed and walking - both in the hospital and when you return home - are vital. Not only do we begin to lose muscle mass within even just one full day of complete bed rest, but staying completely sedentary for more extended periods is a significant risk factor for postoperative complications like blood clots and pneumonia. Walking during the first two weeks postpartum, whether around the house or down and back a few blocks outside, is suggested as long as you have no symptoms. A higher step count has been linked to a decreased risk of in-hospital complications and fewer post-discharge complications for new mothers. Remember, a body in motion will stay in motion.

REFERENCES

World Health Organization. Caesarean section rates continue to rise amid growing inequalities in access. WHO. https://www.who.int/news/item/16-06-2021-caesarean-section-rates-continue-to-rise-amid-growing-inequalities-in-access. Published June 16, 2021.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar. 123 (3):693-711. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Komoto Y, Shimoya K, Shimizu T, et al. Prospective study of non-closure or closure of the peritoneum at cesarean delivery in 124 women: Impact of prior peritoneal closure at primary cesarean on the interval time between first cesarean section and the next pregnancy and significant adhesion at second cesarean. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2006 Aug. 32(4):396-402. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

Rousseau JA, Girard K, Turcot-Lemay L, Thomas N. A randomized study comparing skin closure in cesarean sections: staples vs subcuticular sutures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Mar. 200(3):265.e1-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

A.D. Mackeen et al., “Suture Compared With Staple Skin Closure After Cesarean Delivery, A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Obstet Gynecol, 123:1169–75, 2014.

Zandvakili F, et al. Maternal outcomes associated with caesarean versus vaginal delivery. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2017;11(7):QC01.

Mackeen AD, Sullivan MV, Schuster M, Berghella V. Suture compared with staples for skin closure after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(2):293-303.

Roofthooft E, Joshi GP, Rawal N, Van de Velde M, Joshi GP, Freys S; PROSPECT Working Group* of the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy and supported by the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association. PROSPECT guideline for elective caesarean section: updated systematic review and procedure-specific postoperative pain management recommendations. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(5):665-680.

Spencer JP, Thomas S, Trondsen Pawlowski RH. Medication Safety in Breastfeeding. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(6):638-644.

Kitson-Reynolds E. A guide to caesarean wound healing. Br J Midwifery. 2021;29(Sup8a):1-8.

Zuarez-Easton S, Zafran N, Garmi G, Salim R. Postcesarean wound infection: prevalence, impact, prevention, and management challenges. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:81-88. Published 2017 Feb 17. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S98876

Other Posts You Might Like